I recently came across a very interesting observation made by an artist.

The very Indian caricaturish head bob that the entire west uses for humor may actually have a much deeper meaning.

Let’s talk about it –

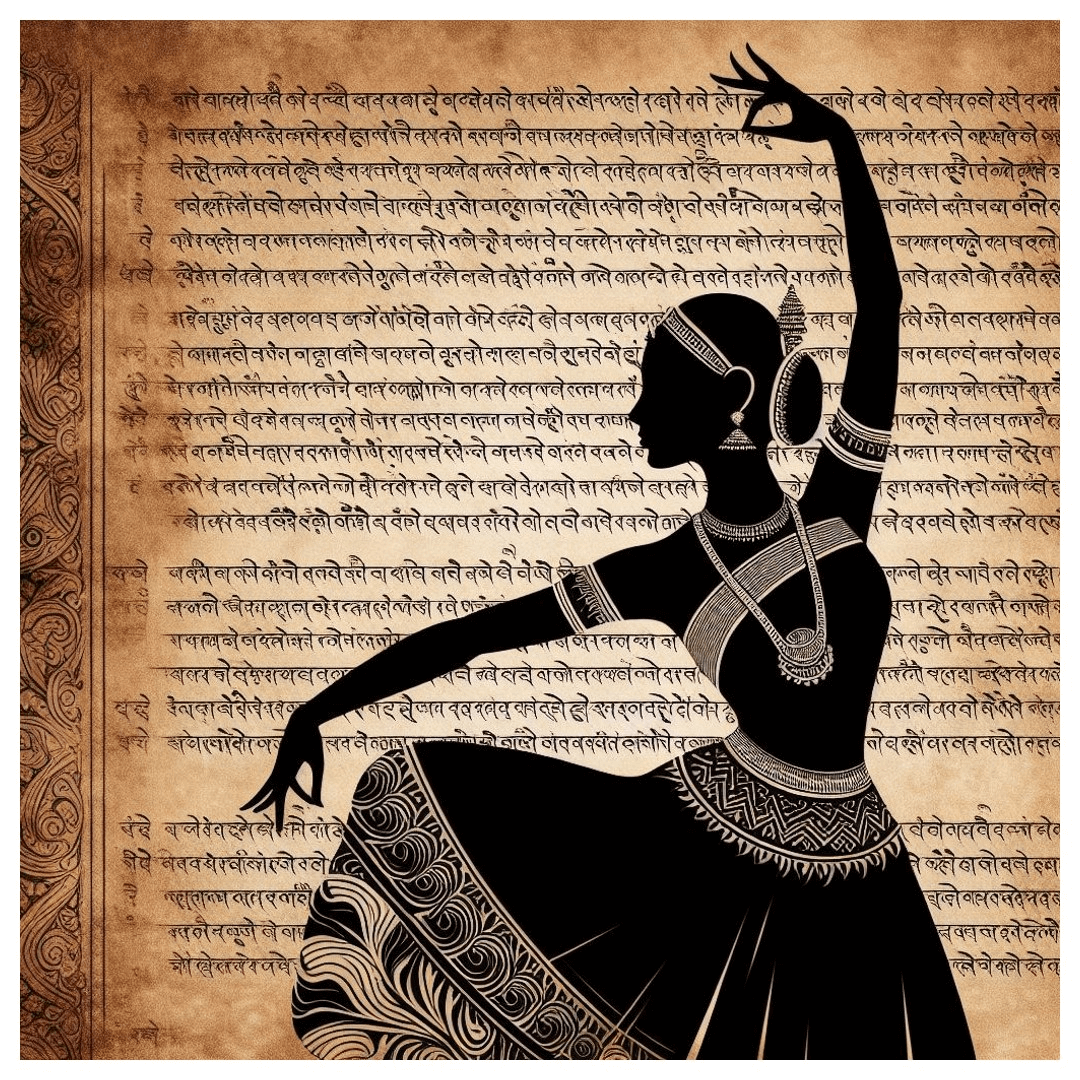

A small stroll within the pages of Natyashastra…

The Natyashastra (नाट्यशास्त्र) written by Bharata Muni is the foundational and definitive ancient Indian Sanskrit text written for performing arts, which encompasses drama, dance, and music. It is essentially an encyclopedia of artistic theory, technical instruction, and philosophy for all aspects of Indian theatre. The composition date is uncertain but is generally estimated to be between 200 BCE and 200 CE, making it over 2,000 years old.

The Natyashastra has explained how the movement of a performer’s neck and head can communicate simple and complex emotions. This concept, rather this classification, comes under shirobheda (types of head movements) and grivabheda (types of neck movements).

To understand the similarities between these concepts and the Indian head bob let us understand what these classifications essentially encompass.

The technicalities…

a) Shirobheda ~

The Naṭyashastra by Bharata Muni meticulously details every aspect of physical expression, Angika Abhinaya, including the highly subtle movements of the head, known as Shirobheda (शिरोभेद)

Shirobheda literally means “classified head movements” and is crucial because the head, being the most prominent feature, helps establish the rasa and the psychological state of the character. Bharata Muni lists nine distinct movements of the head, each used to convey a specific emotion, object, or situation.

- Sama (सम) – Still, straight – looking directly forward. Conveys neutrality, natural state of being, confidence, deep thought, or commencement of performance. It is the default position our heads rest in.

- Udvāhita (उद्वाहित) – Raised – lifting the head up and back. Conveys pride, ascent (going up), heights, looking at the sky, or arrogance.

- Adhōmukha (अधोमुख) – Downcast – bending the head low. Conveys shame, modesty, sorrow, bowing, introspection, or looking at something on the ground.

- Ālōlita (आलोलित) – Circular – a slow, continuous, full circle rotation of the head. Conveys dizziness, frenzy, intoxication, laughter, sleepiness, or being possessed.

- Dhuta (धुत) – Shaken, slow side-to-side – a gentle movement from left to right. Conveys denial, looking around, cold, sorrow, unwillingness, or astonishment.

- Kampita (कम्पित) – Nodding – a quick, sharp movement. Conveying anger, arguing, affirmation (“Yes” or assent), command, or impatience.

- Parāvṛtta (परावृत्त) – Head turned back – a quick turn of the head to one side (left or right).Turning away, looking back. Conveying aversion, avoiding contact, or a feeling of neglect.

- Utkṣipta (उत्क्षिप्त) – Turned to one side and raised – a quick turn to the side followed by a slight upward tilt. Pointing to a direction, expressing acceptance.

- Parivāhita (परिवहित) – Quick side-to-side – a gentle, rapid movement from side-to-side (like the head bob used to express agreement or confusion). Conveying joy, adoration, contentment, pleasure, contemplation, or expressing surprise.

b)Grivabheda ~

The Grivabheda (ग्रीवाभेद) refers to the different movements and positions of the neck (Grivā) as given by Bharata Muni in Naṭyashastra.

The movements of the neck are vital for enhancing the emotional expression (Bhāva) established by the head (Shirobheda) and the eyes (Drishtibheda).

- Sama (सम) – Straight, steady. Conveys neutrality, natural posture, silence, contemplation, or meditation. (The standard, default position.)

- Nata (नत) – Bent down. Conveys sorrow, salutation or carrying a burden.

- Unnatha (उन्नत) – Raised, tilted. Looking up at the sky, viewing distant objects, ascent, or arrogance.

- Tryashra (त्र्यश्र) – Oblique/Tilted neck. Carrying heavy objects, fear, confusion, or expressing distress.

- Rechita (रेचित) – Quick and sweeping movement of the neck, often combined with a head movement to express an energetic state or a dance turn.

- Kunchita (कुञ्चित) – Tucked in/Contracted. To show as if shivering from cold, or expressing sickness/pain.

- Anchita (अञ्चित) – Stretched back. Often related to expressing deep sorrow or a swoon.

- Vahita (वाहित) – Moved to one side. Lifting the shoulder (often due to grief), or expressing pride or contemplation.

- Vivarta (विवर्त) – Turned completely sideways. Moving the head side-to-side to indicate changing perspectives, passion, or looking back quickly.

Head and neck movements are often used as a way to communicate across cultures. However, alot of times the only movements largely used are the yes/no gestures. The Indian head bob is a universal term used for various different Indian head movements that we communicate with. But has anyone stopped to consider that maybe we had cracked the way to communicate more complex emotions and feelings without the use of words, with just the head and neck?

So what does this mean?

Art imitates life or life imitates art is a long standing debate. I think that both the ideas are true. And that would explain the inclusion of the Shirobheda and the Grivabheda in the Natyashastra all those years ago. Whether we were already using these movements that Bharata just classified in the text or we began communicating that way after the Natyashastra; the truth still remains… The Indian head bob may just be thousands of years of learned complex communication that the west just perceived as nothing more than looking funny.

We communicate sympathy, humor, empathy, support, disgust, negativity, disagreement, agreement, pity, understanding, misunderstanding and so much more without uttering a single word.

Human life has been all about community living and being social since the beginning of time. We formed communities and cracked ways to understand each other and communicate. Additionally, it is not a secret that the communities now residing in Bharat are few of the oldest groups to come together and create such a way of living. Keeping this in mind, is it not possible that these oldest communities and civilisations to ever exist found complex ways to transmit information by using their body?

Beyond the caricature : language of precision…

The Indian head bob may be a global caricature, but to dismiss it as mere indecision or a quirk is to ignore a legacy of aesthetic rigor. When viewed through the lens of Bharata Muni’s Natyashastra, the everyday gesture transforms into a vocabulary.

The subtle tilts, nods, and rotations are not random movements; they are codified actions—the Śirōbhēda (head movements) and Grivābhēda (neck movements)—each designed to precisely communicate specific emotions, from affirmation Kampita to subtle joy Parivāhita. Ultimately, the “head bob” is a powerful piece of non-verbal cultural currency. It reminds us that behind every cultural cliché lies a complex, refined back story waiting to be understood.

(Note : This highly nuanced and intelligent observation of connecting the Indian head bob stereotype to Shirobheda from the Natyashastra has not been made by the author of this article. It has been made by a Bharatnatyam dancer online.)